言论自由与漫画自由 言论自由与漫画自由

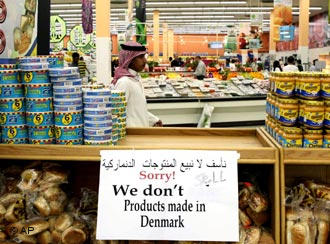

在加沙城,几十名持枪者企图冲击欧盟的办公室。挪威关闭了它在约旦河西岸的办事处。一名德国人遭短时间的绑架。在刊登那几幅伊斯兰先知穆罕默德的漫画前始料不及的。漫画已经引起了全世界穆斯林的广泛抗议。 扪心自问,如果漫画家用漫画来丑化圣子基督,哪位基督徒会没有被伤害的感觉?这在穆斯林也是一样。因此,丹麦“日德兰邮报”刊登了拿伊斯兰先知穆罕默德开心的漫画遭到穆斯林的集体谴责便完全可以理解了。但话又说回来,这也不能成为威胁要杀掉漫画作者的理由。在西方国家中,谁感觉受到了歧视或者污辱,可以通过法律手段解决。 西方国家政教分离的理念对伊斯兰世界来说还很陌生。这就是伊斯兰国家抗议的浪潮一浪高过一浪的原因。当然,欧洲的言论自由是社会的宝贵财富,是基督教欧洲国家的立国之本。但问题是,这种言论自由可以走多远?换句话说,讽刺与污辱之间的界线在哪里?丹麦人划出的界线肯定与信仰伊斯兰教的阿拉伯人有所不同。丹麦人及许多欧洲人习惯于与不信仰基督教的人讨论宗教问题,也包括采用讽刺与漫画的形式。 但笃信伊斯兰教的穆斯林就不习惯这种形式。与12世纪以前的情况不同的是,现今世界的伊斯兰教完全禁止为先知画像。为先知作画本身对穆斯林来说就是一种污辱,是对他们生活目标的一种诋毁,更不用说是轻蔑伊斯兰教的漫画了。 但丹麦的漫画作者及日德兰邮报辩解说,他们绝没有轻蔑伊斯兰教的意思。尽管如此,人们还是责备他们轻率地伤害了宗教感情。日德兰邮报发表类似的漫画只能给言论自由的脸上抹黑。因为西方国家的出版法中做出明确的规定,在发表作品时必须顾及人们的宗教情感。如果人们能够从此次漫画事件汲取教训的话,那就是在交往中要注意尊重对方。 在许多穆斯林人口占多数的国家中,一些冥顽不化的宗教人物利用穆斯林对漫画的愤怒来达到自己的目的。他们拒绝与西方国家对话。漫画的发表对他们来说就是西方国家反伊斯兰态度的铁证。这的确是一派胡言。在欧洲,成百万的穆斯林与基督徒和睦相处。在日常生活中基本没有摩擦。可这一点对许多伊斯兰极端分子来说就是一个挑衅-但与漫画相比,这倒是一个有益的挑衅。

ANALYSIS

Cartoons play into hands of extremists on both sides

Craig S. Smith, New York Times Sunday, February 5, 2006 http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2006/02/05/MNGR1H32TP1.DTL&hw=craig+smith&sn=002&sc=926 Paris -- Europeans hoisted the banner of press freedom last week in response to Muslim anger over a dozen Danish cartoons, some of them mocking the prophet Muhammad. But something deeper and more complex was also at work. The fracas grew out of, and then fed, a war of polemics between Europe's anti-immigrant nationalists and the fundamentalist Muslims among its immigrants. "One extreme triggers the other," said Jonas Gahr Store, Norway's foreign minister, arguing that both sides want to polarize the debate at the expense of the moderate majority. "These issues are dangerous because they give the extremes fertile ground." It began with a decision by a Danish newspaper to commission, and then print, cartoons portraying Muhammad in whatever light cartoonists chose to put him. The newspaper's culture editor, Fleming Rose, says he intended simply to test cartoonists to see whether they were self-censoring their work, out of fear of violence from Islamic radicals. He cited a Danish comedian who said in an interview that he had no problem urinating on the Bible, but that he would not dare do the same to the Quran. "Some Muslims try to impose their religious taboos in the public domain," Rose said. "In my book, that's not asking for my respect, it's asking for my submission." Rose wrote to the Danish Cartoonist Society, inviting cartoonists to depict their interpretation of the prophet -- whose likeness many devout Muslims believe should never be depicted. Some refused on the grounds that the exercise was a provocation, but a dozen complied. Rose said not all 12 drawings would offend Muslims. One depicted a Danish anti-immigration politician in a police lineup, and another lampooned Rose as an agent provocateur. "It wasn't meant to insult or hurt anybody's feelings," Rose said, drawing a distinction between criticizing religious authority, "which goes all the way back to Voltaire and the tradition of the Enlightenment," and the "far greater offense of denigrating a specific ethnic group." But this did not take place in a political vacuum. Hostile feelings have been growing between Denmark's immigrants and a government supported by the right-wing Danish People's Party, which has pushed anti-immigrant policies. And stereotyping in cartoons has a notorious history in Europe, where anti-Semitic caricatures fed the Holocaust, just as they feed anti-Israeli propaganda in the Middle East today. In the current climate, some experts on mass communications suggest, the exercise was no more benign than commissioning caricatures of African Americans would have been during the 1960s civil rights struggle. Nicholas Lemann, dean of the Columbia Journalism School in New York City, put it this way: "He knew what he was doing." The reaction, in any event, was clearly deliberate. A group of Denmark's fundamentalist Muslim clerics lobbied the embassies of 11 mostly Muslim countries to demand a meeting with Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen. When he refused, the clerics took their show on the road, shopping the offending images around the Middle East. The clerics inflamed the response by including in their presentation far more offensive cartoons that never appeared in any newspaper, some depicting Muhammad as a pedophile, a pig or engaged in bestiality. The result: Boycotts of Danish goods spread in the Middle East, while newspapers across Europe reprinted the cartoons as an act of solidarity with Rose's newspaper. And there was agonizing over what it meant for both press freedom and tolerance. "The limit to freedom of expression is the point at which there is an intent to harm a person or a community," said William Bourdon, a French lawyer who has handled important freedom-of-speech cases. "It's not because there was a reaction that there should be a presumption of intent." But Mustafa Hussain, a Pakistani-born Danish sociologist, said the cartoons showed how far to the right Europe's debate has swung. "Switch on the television, and you have the impression that Muslims are all fanatics, that Muslims don't understand Western liberal values," he said. But regardless of whether Rose's exercise achieved his stated goal -- of forcing citizens to think about their submission to someone else's taboos -- it was clear that it had helped extremists on both sides who would keep Europe and the Muslim world from understanding each other.

|