The second Sino-Japanese War compiled by Si Mi Au The fundamental aim of the Tokugawa regime in 1868 was to build a united, prosperous and powerful nation state. Gradually it began to progress towards the domination and colonization of vast tracts of the Asian continent so as to contribute to its immediate strategic interests. An expansive foreign policy could be used, on the other hand, to distract discontents at home and the acquisition of an empire provided one of the indicators of great power status. It became apparent that the Japanese empire was set up as security ring(s) surrounding the ‘core area' of its mainland.

To Japan, there is no consensus as to when the second Sino-Japanese War began. Was it in 1931 with the ‘Manchurian Incident' or the ‘China Incident' in 1937 ?The Japanese leftists saw the Japanese War or the Fifteen Year War as a colonial conquest beginning with the annexation of Manchuria in 1931. Nevertheless, most historians place the beginning of the war on the Battle of Lugou Bridge on July 7, 1937 while Chinese historians place the starting point on the Mukden Incident of September 8, 1931.

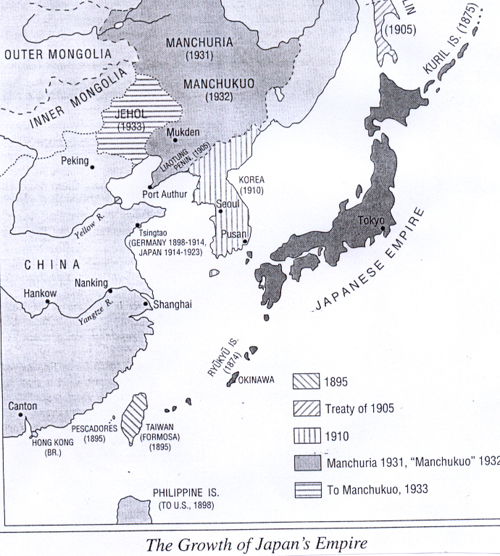

The nineteenth century was the heyday of imperialism. China and Japan were forced to submit to western domination under the ‘unequal treaties'. The Opium War of 1839-42 in which the Chinese forces were demolished by the British. The government in Peking was forced by the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 to open Shanghai, Canton, Ningpo, Foochou and Amoy to British trade and residence, and to cede to Britain the island of Hong Kong. Other western powers negotiated similar treaties later year(s) giving them the same rights in the five mainland ports. One foreign power advanced by land was the Russians. Sensing China's weakness and internal problems, they penetrated in northern Manuchuria which is a region in Northeast Asia, the traditional homeland of the Manchus. In the treaties following the war of 1858-60, the Russians detached the maritime provinces of eastern Manchuria and added them to their empire, plus the port of Vladivostok, which they had founded on the Pacific Coast. Manchuria came under strong Russian influence with the building of the Chinese eastern railway through Harbin to Vladivostok (Pacific naval base of Russia). The Russians occupied Manchuria after the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. The English, wishing to check the Russian expansion in Asia, concluded an alliance treaty with Japan in 1902. No agreement was reached with Russia over their troops staying in Manchuria and the Japanese attacked the Russians on Liaodong and at Mukden as well as from Korea. This is known as Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The Treaty of Portmouth was signed in 1905. Korea was recognised as being under Japanese hegemony and the Russian possession on Liaodong Peninsula were ceded to Japan as well as the railway which went from Lushun all the way up the Liaodong Peninsula onto the interior of Manchuria above Mukden. After the Russo-Japanese War, Japan had become the dominant foreign power in Southern Manchuria though Manchuria was formerly a Russian sphere of expansion ever since the Treaty of Tientsin in 1860. Japan concluded an agreement (Treaty of Portmouth, 1905) with Russia which divided the two countries spheres of influence in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia. Why the location of Manchuria was so strategic? The establishment of the formal empire by Japan had been begun by acquiring Taiwan in 1895, appropriating southern Sakhalin in 1905 and establishing a protectorate over Korea in 1905, followed by its annexation five years later. Such treaty of annexation signed in 1910 was declared to promote ‘the common wealth of the two nations' and to guarantee ‘permanent peace' in Asia. At the end of the Sino-Japanese War, Japan won most-favoured nation status in China and ten years later, at the end of the Russo-Japanese War, she was able to establish a protectorate over Korea and extend her economic interests in south Sakhalin and the South of Manchuria. Japan, like Germany, believed that it was essential to have guaranteed access to the raw materials and markets necessary for industrial success and military vitality. The Japanese leaders saw Russia weakened by famine and China divided by the struggle between Chiang Kai Shek and the Communists. The key to Japan's policy in China was claimed as gaining access to the raw materials there available, to secure a ready market for her goods and to ensure that the resources of that country be attuned to her economic and strategic needs in the event of war against Russia. The operation of the Manchurian Railway by the Japanese from the Liaodong Peninsula onto Manchuria became a vehicle to control Manchuria. By acquiring treaty rights Japan's government had stationed forces in Manchuria, protecting its railroad and other interests. Japan laid the South Manchurian Railway since 1905 which operated in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. The South Manchurian Railway Company developed soy beans, mineral resources and brought them to Japan by this railway. It also built hotels, schools, libraries etc. for Japanese immigrants. The Treaty of Shimonoseki 1895 granted the Japanese sovereignty in Liaotung Peninsula (to the north-west of Korea) and a number of islands including the Chinese province of Taiwan. Port Arthur, built up by the Chinese near the tip of the peninsula, was a valuable naval base within easy range of the China coast and occupying one edge of the Gulf of Pohai with Tientsin on its other western shore. A fleet based at Port Arthur could seal off access to north China and blockade much of the entire coast, while adjacent Dairen was a valuable commercial base. The Japanese Army had powerful forces in neighbouring Korea which they formally annexed in 1910 after victory in the Russo-Japanese War. The neutrality of the area, the ability of Japan to defend its colony in Korea has to be maintained and such explained why the Japanese steadily expanded their influence in Manchuria during the 1920s. All along, what had saved China from a complete colonial takeover was primarily the rivalry among the powers, including Japan. None of them were willing to see any one country become dominant in China. But when Japan was impatient, intending to extract new concessions, naval bases, leased territories and ‘spheres of influence, it started to stir up conquests. Japan's Imperialism Japan was forced open by the Americans in 1853. Though they themselves felt that Japan was a special place, even a superior one, they recognised that the westerners had much of value to offer them. They quickly saw that Japan was far behind the west in almost every respect and could benefit from cultural borrowing. This was the same set of attitudes which had underlain the Japanese borrowing from Chinese civilization from the 8th century onwards. They realised that the new sources of western strength had to be adopted as the only way of defending the country against threat. They were free of the cultural arrogance of China. So under the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese tried to build new western-style strength which could ultimately keep Japan from becoming just another victim of western imperialism. The ‘unequal treaties' which had been forced onto Japan, special privileges for foreigners, extra-territoriality, and an artificially low tariff of 5 percent,, were all to be tolerated. From the early years of Meiji, there was determination to bring about the revision of the treaties and an acceptance of Japan as a diplomatic equal rather than a ‘backward' nation which could be treated like an inferior. Overseas Aggression The Japanese government felt that it was part of the new Japan's destiny to express its strength in East Asia, and as early as 1872, there were plans in Japan to invade Korea, and an actual expedition to Taiwan in 1874, followed by an expedition to Korea in 1876 to open Korean ports to Japanese trade. In 1894 the war was fought between China and Japan over Korea when there was a revolt against the Korean king. The Japan army routed the Chinese forces, occupied the whole of Korea and moved out to invade Manchuria. The Japanese ships sank a large part of the Chinese fleet in a battle off the Korean west coast and damaged or routed the rest. The victorious Japanese dictated the terms of the Treaty of Shiminoseki which ended the war and among other provisions extracted a heavy indemnity from China which was three times the annual income of Peking. The Russians had persuaded the Germans and the French after the signing of the Treaty of Shiminoseki to advise Japan to give up Liaotung. Faced with such pressure, Japan was obliged to do so, but accepted a considerable increase in the indemnity paid by China. There was massive indignation in Japan over this ‘humiliation'. Within three years, Russia took over Liaotung and Port Arthur, the Germans seized Tsingtao in Shantung, the French Kuangchou Bay south of Canton, the British Wei-hai-wei in Shantung (which had originally been part of the Japanese claims) and the United States the Philippines and Hawaii. Japan concluded from all the experience that force was a very effective instrument of foreign policy. In 1902 Japan and Britain signed an Anglo-Japanese alliance of mutual support; Japan accepted the existing treaty system in China and Britain acknowledged that Japan had a special interest in Korea. This was Japan's first agreement with a western power on equal terms and it gave a great boost to morale – the western powers would remain neutral if Japan attacked Russia. Japan, basing themselves on the Western model of imperialism, took over Korea and Taiwan in 1895, replaced the Russians as the dominant power in Chinese Manchuria. It felt that as far as being fed by new power of steam and steel, its country and civilization was ‘superior' to other ‘backward' nations where industrialization had not been spread and these need Japanese civilization to offer them ‘blessings'. It followed the western path of industrialization and consequent military power over the rest of East Asia, whose development was lagging. Japanese had always though of themselves and their country as ‘special'. They now felt that they had a ‘civilizing mission' to perform. New Order There was a statement made by the Prime Minister of the Japanese Government, Konoe Fumimaro in November 1938 which reads – ‘What Japan seeks is the establishment of a new order that will insure the A tripartite relationship ….. between Japan, Manchukuo and China …….

There was a clear appeal in the Japanese ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere' with Japan providing the technical and managerial skills and the rest of East Asia providing the raw materials and labour. The idea of Japanese cultural superiority over other Asian races had been expounded as early as the late nineteenth century and steadily grew in intensity until the end of World War II. When in 1905, Japan became the first Asian country to defeat a Western power, namely Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, this bolstered Japan's confidence in its destiny to lead Asia.

Japan considered colonies to be a basic prerequisite to achieving international prestige and becoming a first-rate country. Series of international affronts to Japanese pride and status provided fuel to Japanese militaristic sentiments such as rejection by the western countries for Japanese' request at the Paris Peace Conference (1919) to have a racial equality clause included in the League of Nations Covenant; passing in 1924 the Japanese Exclusion Act to shut off Japanese immigration into the US. This eventually led to Japan attacking the Western powers to establish the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Japanese terror tactics had failed to persuade the Chinese to surrender while China's regional topography helped to stall Japanese efforts to advance.

Why the War has to be fought

Japan emerged from its feudal past only after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Started with a market economy, caste differences were abolished; farmers owned their own land; people free to buy property and monopolies abolished in favour of free enterprise. As the focus was to build a powerful country, government had to support strategic industries needed by a strong army. To complete the goals of ‘rich country, strong army', the Japanese economy would have to grow and develop rapidly, especially in industry which could support the military.

Economic Recession

Manchuria or better still, China, an outlet Japan dominated the foreign investment scene in Manchuria, and put heavy investment on development projects like The South Manchurian Railway, linking the port of Dairen with Harbin on the east-west Chinese Eastern. Agriculture along the line was commercialised with access to markets; wheat and soy beans were shipped to Japan, via Dairen as well as into world markets. Nearly a million Japanese subjects lived in Manchuria, although most of them were Koreans. Mining projects were also developed along the new rail routes, shipping coal and iron to Japan but also forming the basis of a big, new iron and steel industry centred in the Mukden area, while dams were built on many Manchurian rivers to provide hydroelectric power and irrigation.

Why so brutal?

The Japanese believed that to achieve mastery, they have to continuously fight for world domination. Because they are fighting for a higher order, a sacred mission is ordained by the gods, so everything else is ancillary. Obedience to the Emperor is pre-eminent. Japanese soldiers have been trained and conditioned in their minds that pain and suffering are immaterial for this struggle. This conflict resulted in torment and affliction to those who obstruct its path and its completion. Any obstacles are taught to be brutally oppressed, not only for its enemies but themselves. The indoctrination emphasis is on group loyalty and disregard of the individual, with a willingness to sacrifice their own lives for Japan and the Emperor. To be captured and become a prisoner of war is regarded as being shameful to the highest degree. His mission is more important than his own life or his family. To conclude this essay aims to understand what happened before and during the Second Sino-Japanese War which is not the same as seeking to justify or explain the way that things happened. Were the Japanese justified in their unquestioning obedience, their acquiescence in their leaders' military aggression need hardly to be judged. There is no denying that during the 1930s and early 1940s, Japanese politics became undemocratic, militaristic and aggressive. Those responsible for the running of the country did inflict untold misery on all the many millions of people who found themselves caught up in the Pacific War. Finally do you agree to what has been described as ‘five withouts' in Japanese society – ‧ wealth without joy

|