Topography of Hong Kong Part 1

compiled by Au Si Mei

The topography is extremely rugged and there is little natural flat land. A series of ridges make up the backbone of the Territory, mostly running from northeast to southwest. The highest point is at Tai Mo Shan (957 m) in the central New Territories, followed by Lantau Peak (934 m) and Sunset Peak (869 m) on Lantau Island. Hong Kong’s rugged topography includes a highly indented complex coastline characterised by numerous bays, headlands, peninsulas and outlying islands. Most of Hong Kong's topography is steep and elevated (consisting of volcanic and granitic uplands) falling dramatically to rocky coasts.

The uplands of the southern, central and eastern New Territories contrast with the low-lying alluvial plains of the north-west New Territories. Northeast to east/north-east-trending faults dominate the landscape and dictate the major pattern of ridges and valleys, created by differential weathering along fault lines. North-west trending faults form a subordinate grain, which dominates in the east and south-east. In addition to controlling the orientation of the main valleys, ridges and uplands, this pattern of faults also manifests itself in the shapes of estuaries, channels, bays and headlands around the coast.

Volcanic rocks, which are exposed over about 50% of the land area of Hong Kong, generally form the uplands in western Lantau Island, southern Hong Kong Island, and the central and eastern New Territories. The rocks consist mostly of tuffs, formed by the consolidation of volcanic ash and larger fragments ejected from ancient volcanoes. Volcanic rocks form steep, rugged and angular peaks, such as those of Tai Mo Shan, Sunset Peak, Lantau Peak, the ridge from Kowloon Peak to Tate’s Cairn, Ma On Shan, High Junk Peak, and Sharp Peak. Volcanic tuffs also form steep, cliffed coastlines, like those along the eastern shores of the New Territories.

By contrast, around 35% of Hong Kong lies on granitic rocks, such as those which cover northern Hong Kong Island, eastern Lantau, Kowloon, Sha Tin, the western New Territories, the Lion Rock ridge, and southern Lamma Island. These granites are variable, though the most common form is pink or grey with a medium-to-coarse grain. Other varieties have scattered large crystal in a medium-to fine-grained groundmass. Granites weather differently to volcanic tuffs and form lower more rounded peaks which support little vegetation and which are prone to weathering and erosion. The process of weathering produces 'tors', isolated blocky rocks, boulder fields and severely eroded hillsides known as 'badlands'.

Sedimentary rocks are exposed over about 15% of Hong Kong, mostly in the northern and north-east New Territories. They include sandstones, mudstones, conglomerates, siltstones and shales and are responsible for several distinctive, often red, landforms, such as the low-lying island of Ping Chau and the distinctive Bluff Head Formation of sedimentary rocks on the northern shore of Tolo Channel.

Most hill soils in Lantau Island, Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, the south east New Territories, western and central NT and north east NT are formed from the weathering of either granite or volcanic rocks. The rate of weathering is regulated by the physical properties of the rock, which determine penetration by ground water. In Hong Kong’s hot and wet climate, weathering is very intense and the breakdown of minerals so complete, that dissimilar rocks can produce soils which end up being fairly similar.

One conspicuous feature of granitic soils on many Hong Kong hillsides is the extent of weathering and erosion that has taken place, producing the barren gullied 'badlands' with rather sparse vegetation which are typical of hills in the southwest New Territories. Badlands are generally restricted to areas underlain by granite, where gullies (as in the Tai Lam area) may be as much as 15 m deep. In the north and north-western NT, alluvial soils and sediments dominate the lowland valleys. Many of these areas consist of paddy soil which is poorly drained silt or silt/loam soils suitable for wet agriculture. The structure of these soils has been modified by the processes of ploughing and wet cultivation. In coastal areas (especially the north western NT) soils consist of silty saline soil less suited to arable production.

Development of Hong Kong Landscape

The Hong Kong landscape reflects the complex interaction of natural systems and the development of human civilization. The landscape which is visible today is a relatively recent phenomenon and one that has developed over millennia. When Hong Kong's oldest rocks were laid down (some 400-360 million years ago) the climate was semi-arid. During this period, sedimentary rocks were deposited in larger rivers that crossed an open, un-vegetated, plain from nearby mountains. Rocks from this period are still visible in the North-east New Territories at Plover Cove and along the northern coast of Tolo Channel. Between 360 and 320 million years ago, a shallow topical sea existed across Hong Kong. Coastal swamps were also formed, with deposited organic material producing carbon deposits which eventually formed into graphite. Today, these rocks occur on the Brothers Islands where they were mined until relatively recently.

Between 210-190 million years ago, a deeper marine environment developed, which was succeeded about 165-140 million years ago by a period of volcanic eruptions. Large volumes of volcanic ash and lavas were spread over the land surface, nearby sea inlets and shallow lakes. These volcanic tuffs now underlie almost 50% of Hong Kong, particularly in western Lantau, southern Hong Kong island, south eastern NT and much of the central NT and north eastern NT. Molten magma below the volcanoes cooled and solidified to form the granite rocks which are today exposed over about 35% of Hong Kong and which are particularly common in the western New Territories, Kowloon, northern Hong Kong Island.

Between 100-80 million years ago, a desert climate prevailed and Hong Kong's landscape was dominated by mountains and wide valleys. Rivers crossing the landscape flooded occasionally, leaving sediments of river sands and pebbly conglomerate rocks. These materials now form striking rocks exposed at locations such as Port Island and Pat Sin Leng. Around 80-50 million years ago, the climate remained dry, but shallow salt lakes formed during wetter periods, drying out intermittently. Sedimentary rocks laid down in one of these lakes form the island of Ping Chau on coastal waters off the north-east of Hong Kong.

A warm humid climate over the last 60 million years has caused deep weathering of rocks across Hong Kong, although much of this material has since been removed by erosion. Weathering along joints and the pattern of faults across Hong Kong as well as subsequent erosion has created the rugged landscape of peaks and valleys which forms the basis of the landscape today. During the last 2 million years, sea levels have risen and fallen many times, as glaciers have contracted and expanded in temperate and polar regions. The last major glaciation reached its maximum extent about 20-25,000 years ago, when world sea levels were about 130 metres below present day heights. At that time, the coast of Hong Kong lay about 120 km to the south of its present position. The numerous islands and highly indented coast of modern Hong Kong are part of this drowned landscape.

Shoreline of Hong Kong

As the climate became warmer after last glacial period, sea levels rose, reaching present sea level around 6,000 years ago. This period marked the formation of the existing shoreline of Hong Kong SAR together with the arrival of marine-going human settlers. Though the topography of Hong Kong was largely formed by this time, weathering of rock and erosion of coasts by the sea has continued to this day. In particular, the eastern coasts of Hong Kong have been weathered by wave action into dramatic rock formations whilst the western coasts have been subject to deposition of silt carried down the Pearl River, forming the extensive mudflats landscapes of Deep Bay.

Before the British arrival in Hong Kong, the landscape had changed relatively little in over 2000 years with perhaps the sole exception of the deforestation of almost all the land area. Over the next 150 years, massive and dramatic changes were to occur in the Hong Kong landscape, especially in Hong Kong Island and Kowloon

Reforestation programmes in suburban areas were implemented soon after the arrival by the British in the 1870s. In 1884, 714,159 trees were planted, the vast majority of which were pines. After the British leased the New Territories, Government reforestation was expanded (typically with the plantation of Pinus spp) such as that in the 1910s around Kowloon Reservoirs. The results of these efforts were that by the Second World War, there had been significant reforestation in certain areas of Hong Kong. Much of this work was undone during the War when much land was cleared for firewood.

After the War, the Government again launched reforestation programmes which have been running ever since, in most years resulting in the planting of 200,000 trees and in some years up to 400,000 (Stokes, 1995). By 1990, almost 10% of the HKSAR was covered by woodland, 5% by plantation and around 10% by tall scrubland (Stokes, 1995). Self-seeding of plantation species (most of which are non-native) is probably the cause of the presence of a number of non-native species in the natural landscape such as Acacia sp., Casuarina sp. and Eucalyptus sp.

These programmes, as well as the establishment of Country Parks in 1976 as areas protected from significant development, have done much to re-establish vegetation (although not always native) on Hong Kong's hillsides, and to ensure the conservation of rural landscape character at least in the uplands, although the impacts of these efforts is continually offset by hill fire. Country Parks now cover around 40% of the entire area of Hong Kong.

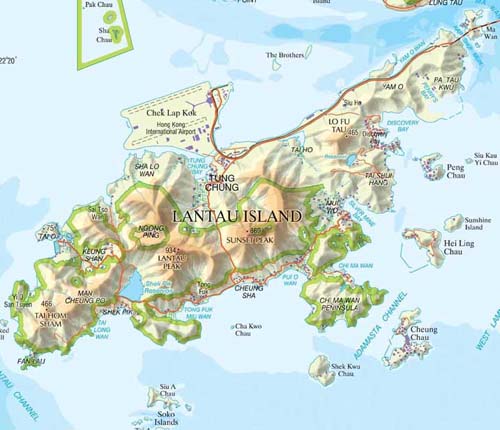

The landscape of Lantau Island is probably that which has been most significantly changed over the last 15 years. The development of Discovery Bay; the Hong Kong International Airport at Chek Lap Kok; Tung Chung new town development; North Lantau Expressway; and Tsing Ma Bridge are all major projects implemented in the last two decades. A number of other major projects were ongoing or in the planning, feasibility or construction stage at the time of the completion of the PLCM survey in 2003. These included the Disneyland theme park at Penny’s Bay, Hong Kong-Macau-Zhuhai Link; Logistic Park, Tung Chung Road; Port Development and Prison at Hei Ling Chau / Silvermine Bay. Other development projects in southern Lantau have been mooted and discussed in the press, including retail and tourism-related uses.

Hong Kong Island

like its underlying geology, is a landscape of two halves. The southern parts of the Island lie on volcanic tuffs forming a series of high peaks which fall steeply to the coast in a series of bays and headlands, notably at Cape D'Aguilar and Chung Hom Kok. These areas are comparatively unpopulated with a significant settlement at Aberdeen and large villages at Stanley and Shek O. By contrast, the northern part of the Island lies on granitic rock and where the two rocks meet in the centre of the island, a steep ridge of hills is formed which includes Victoria Peak (552mPD), Mount Parker (532mPD) and Mount Kellett (501mPD).

South-east New Territories

a mountainous and largely coastal one, which lies mainly on volcanic rocks forced upwards by geological action to forms high, steep peaks. These have weathered in many cases into jagged angular forms, such as those at Ma On Shan, Pyramid Hill and Sharp Peak. These uplands support little significant vegetation and fall precipitously to a rocky indented coast, characterised by its spectacular coastal rock formations, of cliffs, sea arches and stacks.

The numerous offshore islands along the coast form a landscape characterised by the complex relationships of land, sea and sky. Due to its mountainous terrain and coastal location, these landscapes are sparsely settled (Sai Kung and Tseung Kwan O are the only settlements of any size) and often retain a distinct sense of remoteness and transquillity. Isolated villages lie in valleys along the coast and the only significant human feature of any size is the spectacular High Island Reservoir. Only at Tseung Kwan O has there been significant development, with the ongoing construction of the New Town, port and industrial facilities.|

Saikung Peninsula is an area of rolling mountains and tor-topped hills, with some superb coastline and beaches.

Long Ke Wan, Sai Kung, south east New Territories

Landscape Characteristics

• Dramatic grass-covered uplands, rising to steep rigged peaks such as those at Ma On Shan and Sharp Peak. These uplands are almost entirely undeveloped and possess a distinct sense of remoteness

• Highly weathered tors (standing boulders) and rock forests on the upper parts of uplands, notably on Ma On Shan.

• Precipitous coastal landscapes characterised by a series of dramatic bays, headlands and offshore islands. Coastal rock weathers into spectacular cliffs, sea arches and stacks.

• Little settlement and limited road network due to the highly isolated nature of the Terrain

• A pattern of isolated valley landscapes. These are wooded in upper parts with rocky streams tumbling down them, typically with small settlements on the floor (traditionally stone-built dwellings) though fields and houses are often totally or partly abandoned.

• The coastal strip between Clearwater Bay and Sai Kung has been increasingly developed for residential, recreational and other transitional uses.

• The new town of Tseung Kwan O and associated reclamation and urban fringe development in Junk Bay.

The North-east New Territories

The north east NT landscape is one of high uplands and ridges falling in the east to a remote rocky indented coast. The uplands, dominated by the central mass of Tai Mo Shan, Hong Kong's highest mountain, are separated by wide alluvial valleys formed along north-west and north-east trending geological faults. The volcanic tuffs on which the uplands lie form rugged dramatic peak and ridge landscapes, as at Pat Sin Leng and Wong Leng (639mPD). In the east, there are rolling uplands which fall to tranquil coasts characterised by remote valleys, rocky headlands and offshore islands, typified by the landscape of Double Haven. These striking remote landscapes are characterised by the relationships of land, sea and sky as well as by their striking coastal rock formations.

By contrast, the wide alluvial valleys to the west comprise comfortable lowland landscapes. Formed by sediments washed down valleys and flood plains, they were until recently, fertile small-scale agrarian landscapes, typified by those at Long Valley, Lam Tsuen Valley and Sha Tua Kok Valley. These areas are today undergoing extensive change as agricultural land is increasingly abandoned and land uses such as open storage, railways, flood alleviation projects and residential development become more prevalent. The new towns of Fanling, Sheung Shui and Tai Po lie in these lowland and valley landscapes.

Lo Wai, Lung Yeuk Tau, north east NT

Key Landscape Characteristics

• Dramatic grass-covered uplands, rising to steep rugged peaks and ridges such asthose at Pat Sin Leng and Tai Mo Shan. Almost entirely undeveloped, they possess a distinct sense of remoteness

• Tranquil coastal upland landscapes characterised by a series of remote bays, headlands, offshore islands and striking coastal rock features (including sedimentary rock formations, sea arches and sea caves);

• Little settlement and limited road network due to the highly isolated nature of the terrain.

• A pattern of wide alluvial valleys separating the uplands, trending north-west and north-east, such as the Sha Tau Kok, Fan Kam and Lam Tsuen Valleys.

Formerly fertile agrarian landscapes characterised by small scale patterns of villages, fungshui woodland, and fields, this landscape is undergoing change from agriculture totransitional land uses (typically open storage).

• Major transportation corridors, such as the KCRC Eastrail, Tolo Highway and Fanling Highway.

• New town developments at Fanling / Sheung Shu and Tai Po, together with associated urban fringe development of industrial estates and residential development.

• Walled villages ('wai') and traditional rural settlement patterns in the lowland valleys.

• Numerous waterways, formerly meandering streams and rivers, many of which have been canalised in recent years for flood prevention purposes.

North-west New Territories

The north western NT landscape consists of barren granitic uplands in the south and an area of expansive coastal lowlands bordering Deep Bay in the north. The uplands of the south lie on highly weathered granite which forms sets of low rounded uplands and peaks such as those at Castle Peak and at Tai Lam. These uplands are subject to chemical weathering and erosion which results in hillsides being marked by deeply eroded gullies and scars, a phenomenon known as 'badlands'. They therefore support little vegetation and are often barren and undeveloped.

To the west, the uplands fall gently to the remote and tranquil coast of Deep Bay. To the north lies a landscape of wide valleys and coastal lowlands, much of it having been extensively reclaimed from Deep Bay over the course of centuries. These landscapes are characterised by fish ponds or gei wai as at San Tin and Mai Po or by arable agriculture in inland areas such as Kam Tin or Pat Heung. Until relatively recently, these were intact agricultural landscapes of fields, small villages and meandering streams. Changes in land use from agriculture or fish farming to open storage and residential development mean it is a landscape in the process of change. This includes development of new towns and developments at Tuen Mun and Tin Shui Wai as well as the gradual loss of traditional rural land uses.

Nam Sang Wai and Deep Bay, north western NT

• Rolling, barren uplands at Castle Peak and Tai Lam, characterised by high levels of weathering and erosion ('badlands') with limited vegetation cover.

• Remote, tranquil coasts between Tuen Mun and Tsim Bei Tsui, characterised by remnant arable fields, small villages and blocks of woodland.

• Low-lying coastal landscapes on the edge of Deep Bay, consisting of extensive areas of mudflat, fish pond, gei wai, reed bed and mangrove.

• A pattern of wide alluvial valleys and lowlands, separating the uplands, trending north-west and north-east, such as the Kam Tin and Tuen Mun Valleys. Formerly fertile agrarian landscapes characterised by small scale patterns of villages, fung shui woodland, and fields, this landscape is undergoing change from agriculture to transitional land uses (typically open storage).

• Major transportation corridors, such as Tuen Mun Road, Castle Peak Road, Route 3, KCRC West rail and San Tin Highway.

• New town developments at Tuen Mun, Tin Shui Wai and Yuen Long, together with associated urban fringe development of industrial estates and residential development

• Walled villages ('wai') and traditional rural village settlement patterns in the lowland valleys

• Numerous waterways, formerly meandering streams and rivers, many of which have been canalised in recent years for flood prevention purposes.

Kowloon/Tsuen Wan/Sha Tin

The landscape of the Kowloon/Tsuen Wan/Sha Tin area consists of a series of high ridges of granite rock north of Kowloon, together with associated urban development between this ridge and Victoria Harbour. The granites form steep rolling uplands on either side of the Sha Tin Valley and a distinctive ridge of peaks that forms the dramatic backdrop to Kowloon. Below these uplands lies one of the world’s most densely populated urban landscapes, consisting of the Kowloon Peninsula and the urban areas that spread out from it to the west as far as Tsuen Wan and Tsing Yi and to the east as far as Lei Yue Mun.

Urban development has been facilitated by extensive areas of reclamation along the coast which now forms medium rise urban landscapes developed to a regular grid of streets and urban blocks in areas such as Sham Shui Po, Yau Ma Tei or To Kwa Wan. The urban landscapes of Kowloon are of widely differing character and quality and include extensive dockside and waterfront landscapes in Kwun Tong and Kwai Chung, low-rise suburban landscapes of Kowloon Tong, vibrant retail streetscapes at Yau Ma Tei and Mongkok and prestigious commercial urban landscapes in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Kowloon Peninsula

Key Landscape Characteristics

• The Devil's Peak to Golden Hill Ridgeline, an area of rugged granitic uplands characterised by scrub and grass vegetation and limited development save for communications features on peaks.

• The Shing Mun Valley where a north-east trending fault has eroded to produce a wide valley with scrub covered hillsides falling from the Shing Mun Reservoirs to Tolo Harbour.

• The Kowloon Peninsula forms an undulating spine to the peninsula between Tsim Sha Tsui and Kowloon Tong. It is characterised by rolling topography, low building densities and high incidence of historic buildings, public institutions and open space.

• The granitic island of Tsing Yi off the western coast of the Kowloon comprising a steep largely undeveloped upland core with urban and industrial development along its shores.

• Extensive reclamation landscapes, situated on the shores of the former Kowloon peninsula reclaimed from Victoria Harbour and generally based on an orthogonal grid, these are some of the most dense and vibrant urban landscapes in Hong Kong.

• Major transportation corridors, such as the West Kowloon Expressway, Cross-Harbour Tunnels as well as the Tsing Ma and Ting Kau Bridges.

• New towns and new development areas at Tsuen Wan, Kwai Tsing, Tsing Yi and Sha Tin.

|