粟特人 - 留在中國境內絲綢之路的書信

區仕美資料整理

粟特是東伊朗人的一支,在古波斯時期,是帝國的行省之一,他們的首府是撒馬爾干(Samarkand) 在貝希斯敦銘文及蘇薩宮廷銘文裡都提到粟特,他們曾向大流士進貢青金石和紅玉髓,這些是阿富汗的產品,可見他們很早就從事東西方貿易了.在亞歷山大東征期間,粟特人曾奮起反抗,多次給馬其頓遠征者造成重大傷亡,亞歷山大費了很大氣力才征服他們.

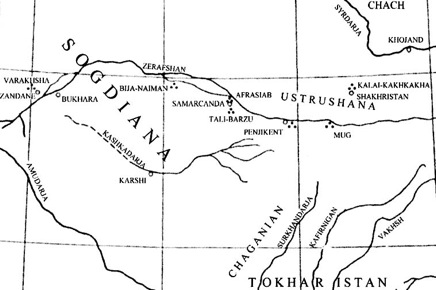

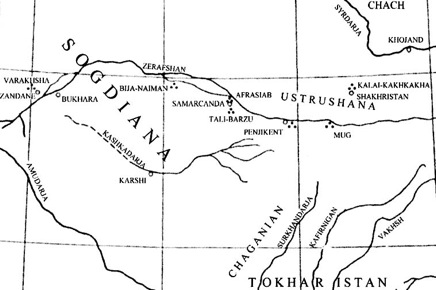

粟特人的本土位於中亞阿姆河和錫爾河之間的澤拉夫珊河流域,即西方古典文獻所說的粟特地區(Sogdiana,音譯作 “索格底亞那” ),其主要範圍在今烏茲別克斯坦,還有部分在塔吉克斯坦和吉爾吉斯斯坦。在粟特地區的大大小小的綠洲上,分佈着一個個大小不同的城邦國家,其中以撒馬爾干(Samarkand)爲中心的康國最大,它常常是粟特各城邦國家的代表。此外,以布哈拉(Bukhara)爲中心的安國,也是相對較大的粟特王國。還有,位於蘇對沙那(Sutrushana/Ushrusana)的東曹國,劫布呾那(Kaputana)的曹國,瑟底痕(Ishitikhan)的西曹國,弭秣賀(Maymurgh)的米國,屈霜你迦(Kushanika)的何國,羯霜那(Kashana)的史國,赭時(Chach)的石國等等,不同時期,或有分合,中國史籍稱他們爲 “昭武九姓”,其實有時候不止九個國家。

粟特人在歷史上從來沒有建立過統一國家,一直依附於鄰近的大國,他們也使用不同的文字來拼寫自己的語言,有阿拉米字母的粟特文,有摩尼字母的粟特文,有景教敘利亞字母的粟特文,不同宗教的粟特人使用不同的粟特語方言,粟特內部宗教派別眾多,但大多數居民是祅教信徒。

在中亚或是在粟特本土发现的考古文物材料,比如像瓮棺、壁画、金银器皿等,可認識粟特人在中国的生活; 从1999年开始,以虞弘墓的发现为肇始,随之而来的是安伽墓、史君墓、康业墓,这一系列重大发现,对于我们这些对粟特感兴趣的学者而言,真的可以说是赶上了一个很好的时代。由于这些粟特人墓葬都经过科学的考古发掘,因而使得我们可以重新判定原本在天水、青州、安阳出土以及流散在外的Miho美术馆所藏同类考古材料的粟特属性。

粟特人建立过许多绿洲城邦,但从没有建立过统一的国家,因此长期受周边的强大外族势力的控制。由于粟特地区处于中亚西部丝绸之路的干线上,粟特人成为了一个独具特色的商业民族,他们通过漫长的丝绸之路频繁往来于中亚与中国之间,成为中世纪东西方贸易的承担者。

善于经商

粟特人以善经商闻名,多豪商大贾,操印欧系东伊朗语,早就创立了源自阿拉美字母系统的拼音文字,一般称之为粟特文,一作牵利文,于阗塞语中称为suli人,即牵利人(粟特人),其复数形式则为suliya,在于阗诸佛教文献中,suliya一词意为商人,这恰恰说明粟特人是以经商闻名于世的。史载康国粟特 “善商贾,好利,丈夫年二十去旁国,利所在无不至”。不辞劳苦,沿丝绸之路东西往返,由之形成了许多粟特聚落。例如丝路北道的碎叶城应即粟特人所筑,入唐后王方翼扩其形制,招徕胡贾,定为北道征收过往商税的关卡所在。后又置为碎叶州,州刺史安车鼻施名见

于神龙元年所建之乾陵蕃臣碑题铭。安指安国,此人似即出身安国的突厥化粟特人。

留在中國境內絲綢之路的書信 ANCIENT LETTERS, name conventionally applied to a group of Sogdian paper documents; discovered in 1907 by Sir Aurel Stein. They were found in the ruined watchtower on the Chinese frontier wall which formerly guarded the route between Tun-huang and Lou-lan. The group consists of five almost complete letters and a number of fragments of similar letters. one letter was wrapped in silk and enclosed in an envelope of coarse cloth addressed to Samarkand, 2000 miles to the west. From the letters themselves it may be deduced that at least two were written in Tun-huang and one in Kutsang. The inference that they represent the contents of a “mailbag” lost or abandoned in transit from east to west accords well with the general tenor of the letters, which seem to consist largely of reports to wealthy Sogdian merchants by their representatives abroad.

The date attributed rather to the beginning of the 4th century, the letters retain their importance both as primary sources for the early history of the silk route and as the most ancient monuments of the Sogdian language.

The only one of the Ancient Letters which provides precisely datable information is the second, which alludes (lines 10-19) to rumors that the Chinese emperor had fled from his capital Lo-yang, due to fighting between the Chinese and the Huns (Sogd. xwn), and to the destruction of the cities of Lo-yang and Yeh. According to W. B. Henning these details are compatible only with events at the beginning of the 4th century: the sack of Yeh in 307 A.D., the attempted flight of the emperor, and the destruction of Lo-yang by the Huns (Chin. Hsiung-nu) in 311 A.D. Henning’s conclusion that the letters were written in the years 312-13 A.D. has been generally accepted. A recent attempt by J. Harmatta to refer the letters to the period immediately following an earlier sack of Lo-yang (not by the Huns) in 190 A.D. appears less soundly based.

The references in this letter to political events in China are too brief to add significantly to the detailed accounts in Chinese annals. However, the equation of xwn with Hsiung-nu is of major historical importance, since it goes a long way towards establishing the sometimes disputed identity of the name of the Far Eastern Hsiung-nu with that of the Huns of Europe.

Other nationalities mentioned in the letters are the Chinese (cynt), Sogdians (swγ’ykt) and Indians (yntkwt), i.e., the Indian inhabitants of Lou-lan, who evidently had close commercial and cultural relations with the Sogdians. Most of the personal names of the merchants and their dependants are Sogdian, but the Iranian names, which include several compounded with the name of the goddess Nanai, provide information concerning the indigenous religion of Sogdiana.

All the places named in the Ancient Letters (insofar as they can be certainly identified) are located along the trade route, known as the silk route, linking central China with the West . In some of these cities there were substantial colonies of Sogdian traders, as is shown by a reference to “100 freemen from Samarkand” (letter 2, lines 19-20). Since many of the letters are concerned with commercial matters, they are potentially sources of the first importance for the economic history of the silk route. Linguistic problems and the incomplete state of preservation of the letters unfortunately make it difficult to follow the details of the transactions involved.

The script of the Ancient Letters is less cursive than that found in later Sogdian documents (of the 8th century onwards) and represents an intermediate stage between this and the Aramaic script from which it ultimately derives.

The Sogdian commercial network grew sufficiently to ensure that in the early 3rd century, in Gansu, the representatives of Kushan and Sogdian merchants were placed on the same level and together participated in political negotiations (Sanguo zhi, chap. 4, p. 895). However, the main proof of Sogdian commercial expansion in the direction of China is provided by a set of letters, the Sogdian Ancient Letters (tr. Sims-Williams, 2001; Grenet, Sims-Williams, and de la Vaissière, 2001). Written in 313 in the Gansu corridor, these show the presence of Sogdian merchant communities in the main cities of the region, as well as in inner China. They also show that the merchants were organized within networks. The second letter, written in Gansu, is addressed to Samarkand.

The descendants of the Kushan rivals are also mentioned in this text, since the Indian (ʾyntkwt) and Sogdian communities of Luoyang had been decimated by famine. It is hard to tell what became of the great trade during the following century, but in 439 the Sogdian merchants were the main foreign merchants in Gansu

From the same period, in the passes of the High Indus, are found more than 600 inscriptions by Sogdian caravaneers, against only about ten Bactrian inscriptions (Sims-Williams, 1989, 1992)—a fact which gives evidence of the replacement of Bactrian merchants by Sogdians.

Growth.

From the 5th to the 7th century, the Sogdians were the principal long-distance caravan merchants in Central Asia. To begin with, their main destination was northern China. From the 5th century on, this area was the goal of a constant flow of Sogdian migrants who settled in the main towns, some of them managing to play a sufficiently important part to be mentioned in the sources or to leave behind epitaphs in Chinese summarizing their careers (examples in Forte, 1995, pp. 42-63; Rong, 2000; de la Vaissière and Trombert, 2004). There were at this period powerful Sogdian communities, led by “caravan chiefs” (sartapao, transcribed sabao in Chinese, Dien, 1962), whose hierarchy became part of the Chinese Mandarin system from the mid-6th century on (Suishu, chap. 27, p. 756 and chap. 28, pp. 790-791; de la Vaissière and Trombert, 2004).

We do not know whether the 3rd- and 4th-century communities of inner China (as in Gansu) were continuations of the earlier ones or were newly created. The Sogdians were familiar personalities in the large Chinese cities and are represented by innumerable Tang statuettes with beards and prominent eyes and noses. Tombs of Sogdian merchants have been found, featuring sumptuously decorated funerary beds in stone.

Until the mid-8th century, the Sogdian trade network was the main continental medium for export and import of luxury products in China and so controlled the principal transasiatic trade route. In Alexandria in 550, the Nestorian Cosmas Indicopleustes pointed out that it was by caravan routes, rather than by sea, that Persia received most of its silk (Cosmas Indicopleustes, II, pp. 45-46). The conquest of Central Asia by Chinese armies no doubt changed the economic conditions within which the Sogdian merchants operated. From 640 to 755, importations of western luxury products increased even more (Schafer, 1963); but with a view mainly to finance their expansion and pay their troops, the Tang empire sent more than 10 percent of its fiscal receipts to the West, for the most part in the form of silk and hemp rolls (Trombert, 2000, pp. 108-9)—a manna from which the Sogdians benefited as the main intermediaries of this great trade.

The other great zone of expansion of Sogdian trade was the steppes. We have no sources directly dealing with trade in the steppes during the early Middle Ages, but the Chinese and the nomadic powers often used Sogdian merchants as gobetweens, and this provides us with some information about their activities. From their bases in Gansu and Turfan, the Sogdians set off as small peddlers traveling among the tribes from the 5th century on and perhaps even much earlier (Wei shu, chap. 103, p. 2310; de la Vaissière, 2002, pp. 202-4).

The Sogdian language loaned to Turkic certain significant words (Old Turkic borč “debt,” Sogd. pwrc; or Uighur styr “coin,” Sogd. styr). The birth of the Turkish empire and its extension throughout the entire steppes greatly contributed to the economic power of the Sogdian merchants. They provided the Turks with their first chancellery language and administrative infrastructure.

The first known Turkic inscription, at Bugut in Mongolia, is in Sogdian (Klyaštornyj and Livšic, 1972 **), and the first historical text to mention the Turks from the standpoint of the Chinese connects them with the Sogdians (Zhou shu, chap. 50, p. 908). Menander Protector’s history does likewise on the Byzantine side; in particular, it reports an actual case, within the period 568-75, of how the Sogdians used their diplomatic influence with the Turks to open up new markets.

After failing with the Sasanians, the Sogdian merchants persuaded the ḵāqān to get in touch with Byzantium in order to export the thousands of silk rolls which China paid as tribute to the Turks (Menander, tr. Blockley, pp. 111-15). Under Turkish protection, and later under that of the succeeding states, the Sogdians established themselves within the trade of the western steppe. In the 7th century, when a trading entrepôt under Khazar protection was founded in the Crimea, it bore the name Sogdaia. During this period almost half of the Sasanian and Central Asian silver dishes found near the Urals had gone through Sogdian or Khwarezmian hands, and in the 8th century, three-quarters had done so (de la Vaissière, 2000, pp. 368-69). Sogdiana was the center where some of the luxury fabrics imported by Byzantium and the West were traded at that time (Shepherd and Henning, 1959).

Fragment of one of the 4th century letters written by an abandoned Sogdian wife.

(Found in a mislaid post bag near Dunhuang.)

Miwnay with her children dutifully followed her husband Nanaidhat, a merchant trading along the Silk Road, to the city of Dunhuang. Both were Sogdians, a group who emerged as a power at the center of the trade routes at the end of the second century CE. Sogdiana lay between the Amu Darya (Oxus River) and the Pamir Mountains in what today is Uzbekistan. The Sogdians ability to reap profits from trade along the Silk Roads lead them to established communities in regions as far east as Chang’an, (today’s Xi’an) and far west as Constantinople.

Unfortunately, after the collapse of the Chinese central government, wars and famine reached Dunhuang. Nanaidhat left the area, traveling off with his caravan, and somehow never retunred, leaving Miwnay for three years. Left destitute, well-to -do Miwnay was forced to become a servant of the Chinese while her daughter Shayn ended up guarding their flocks of domestic animals. With no one in the Sogdian community willing to help them, Miwnay wrote letters to her husband and mother, who apparently never answered nor sent money.

Letter to Nanaidhat: "I obeyed your command and came to Dunhuang and did not observe my mother's bidding nor that of my brothers. Surely the gods were angry with me on the day when I did your bidding! I would rather be a dog's or a pig's wife than yours!"

Letter to her mother: “I am very anxious to see you, but I have no luck. I petitioned the consular Sagharak, but the consular says: Here there is no other relative closer to Nanaidhat than Artivan. And I petitioned Artivan, but he says Farnkhund ... And Farnkhund says: If your husband's relative does not consent that you should go back to your mother, how should I take you? Wait until ... comes; perhaps Nanaidhat will come. I live wretchedly, without clothing, without money. I ask for a loan, but no-one consents to give me one.”

Letter from Shayn to Nanaidhat: “From (his) daughter Shayn to the noble lord Nanai-dhat, blessing (and) homage. And (it would be) a good [day] for him [who] might see [you] healthy, rested (and) happy. ... I have become ... and I watch over a flock of domestic animals. Differently to you, I had a ..., and ... went out. I am ... and I know that you do not lack twenty staters(?) to send. It is necessary to consider the whole (matter). Farnkhund has run away; the Chinese seek him but do not find him. Because of Farnkhund’s debts we have become the servants of the Chinese, I together with (my) mother.”

|